E tem gente que tem saudades destes subservientes.... Bem, Nelson Rodrigues explica!

Aplausos para Celso Amorim, o maior Chanceler da história de nosso país!

São Paulo, segunda-feira, 29 de novembro de 2010

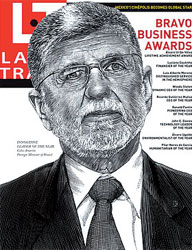

AMORIM, "PENSADOR GLOBAL"

NELSON DE SÁ

Edel Rodriguez/foreignpolicy.com

Dividindo a capa da nova "Foreign Policy" com Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Barack Obama, Ben Bernanke, Hillary e Bill Clinton, entre outros, o chanceler brasileiro Celso Amorim foi eleito o sexto "pensador global" pela revista americana. Seu perfil diz que foi escolhido "por transformar o Brasil em um ator global".

Com a ilustração ao lado, Amorim concede longa entrevista, a principal da edição de dezembro, à própria editora da "FP", Susan Glasser, que viajou a Brasília para falar com ele. Defende o potencial do Brasil como mediador global. A lista traz ainda, em 32º lugar, com outros três ambientalistas, Marina Silva.

latintrade.com

Visto como descartado por Dilma Rousseff no Brasil, Amorim acumula entrevistas e premiações, do espanhol "La Vanguardia" à revista americana de comércio hemisférico "Latin Trade". Na capa mais recente, semanas atrás, a "LT" elegeu o chanceler como "líder inovador do ano", justificando ser "um diplomata que faz a diferença"

Foreign Policy presents a unique portrait of 2010's global marketplace of ideas and the thinkers who make them.

DECEMBER 2010

6. Celso Amorim

for transforming Brazil into a global player.

Foreign minister | Brazil

Celso Amorim wouldn't crack a smile at the old canard that Brazil is the country of the future, and always will be. The wily and urbane Brazilian diplomat, finishing off his second term as foreign minister, has done his utmost to make his country an international powerhouse -- right now.

Neither reflexively opposing the United States in the style of Latin America's old left nor slavishly following its lead, Amorim has charted an independent course. He has criticized developed countries as hypocritical and advocated that developing countries take a leading role in combating climate change. This year, he teamed with an unlikely partner, Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu (No. 7), to cut an eleventh-hour deal designed to dial down the international tension over Iran's nuclear program. Although the initiative succeeded mostly in setting teeth on edge in Western capitals, it also put Brazil on the map.

Under Amorim's guidance, Brazil has enthusiastically embraced the BRIC alliance with Russia, India, and China, which he thinks has the power to "redefine world governance." Brazil aspires to a permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council; in the meantime, it has built up its diplomatic corps and boosted its contribution to international peacekeeping missions in places like Haiti. Amorim's tenure under Brazil's larger-than-life retiring president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has proved that it is possible to have, as he recently put it, "a humanist foreign policy, without losing sight of the national interest."

Read more: Celso Amorim talks to FP about Brazil's role as the rest rises.

FABRICE COFFRINI/AFP/Getty Images

Susan Glasser, Foreign Policy's editor in chief, met Foreign Minister Celso Amorim in Brasilia for a wide-ranging conversation on Brazil's role as the rest rises. Below, the edited excerpts.

INTERVIEW BY SUSAN GLASSER | DECEMBER 2010

Celso Amorim: I would say, of course it's a negotiating power. But it would be very simplistic to think Brazil always looks for consensus for consensus's sake. We also have a view of how things should be, and we tend to work in that direction. We struggle to have a world that is more democratic, that is to say, more countries are heard on the world scene -- a world in which economic relations are more balanced and of course in which countries in different areas can talk to each other without prejudice. And that's what we try to do in our foreign policy.

But of course Brazil is also a big country with a big economy, a multitude of cultures, and in a way similar to the United States -- but also in some ways different because the way people got here and the way they mixed was slightly different. So, Brazil has this unique characteristic which is very useful in international negotiations: to be able to put itself in someone else's shoes, which is essential if you are looking for a solution.

SG: What does Brazil want from the world right now, and what are you prepared to give to get it?

CA: Well, we give engagement. We give our minds, our thoughts. This costs quite a lot. I could be using -- President Lula, myself, and all others could be using our brains for other purposes, political or economic or whatever. Brazil still has many problems. Inequality is still very big. It diminished a lot during President Lula's government, but it's still very big. So there is a long way to go. We know our shortcomings. If you look around, you'll see more women ambassadors and so on; you'll see some black people; but there is still a long way to go. But in any case, we have also this capacity to discuss and to have dialogue which was helpful in our own evolution and has helped in our relations with South America, and I think can help with the world at large.

SG: You make a great case for Brazil as a sort of global negotiator with hopes for a permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council. But to what extent is that a strategy for your country, or is it really a tactic?

CA: Well, having a seat at the table is a means to have your voice heard and to have your ideas heard -- because we believe in them. In the same way that you believe in the American Dream, we believe in the Brazilian Dream and also how the Brazilian example can be useful for others. And maybe because we came after we can do that maybe with some more humility, which helps. We'll never have the military power that gets near to that of -- not even to speak of the United States -- but Russia or China. We'll have to have some military power because that is essential for any state as long as the nation-state exists. But we are aware that it cannot be at that level.

In the present-day world, military power will be less and less usable in a way that these other abilities -- the capacity to negotiate based on sound economic policies, based on a society that is more just than it used to be and will be more just tomorrow than it is today -- all these are things that help. I don't think there are many countries that can boast that they have 10 neighbors and haven't had a war in the last 140 years.

SG: So you're the ultimate soft-power power.

CA: There have to be some hard elements in it, as well: economic growth, as I mentioned, and we have to have some military power, some deterrent military power. Not because of the region; we don't think anything can happen, actually. [Latin America is] quickly becoming what I choose to call a "security community" in which war becomes inconceivable. But if other conflicts happen between other countries, we have to be prepared that it doesn't come to us. So some modicum of military power is necessary. It's not totally soft. People also say we have our music; I won't say our beautiful women because that would sound not very like a --

SG: Retro, not the future.

CA: Exactly.

----------

Data: 16 de agosto de 2010 02:15Bravo! Aplausos para o nosso Ministro das relações Exteriores!

Folha de São Paulo, 15/08/2010

Dedo acusador pode render aplauso, mas raramente salva CELSO AMORIM

ESPECIAL PARA A FOLHA

Têm sido frequentes as críticas que apontam para uma suposta "indiferença" -ou mesmo "conivência"- da diplomacia brasileira diante de países acusados de violar os direitos humanos. Trata-se de um juízo equivocado.

O Brasil deseja para todos os demais países o que deseja para si -a democracia plena e o respeito aos direitos humanos, cuja consolidação e aperfeiçoamento têm sido uma das preocupações centrais do governo do presidente Lula.

Consideramos, entretanto, que as reprimendas ou condenações públicas a outros Estados não são o melhor caminho para obter esse resultado. Na verdade, escolher a intimidação em detrimento da persuasão é quase sempre ineficaz, quando não contraproducente.

O dedo acusador pode render aplausos ao dono, mas raramente salva o jornalista silenciado, o condenado à morte, o povo sem acesso à urna ou a mulher privada de sua dignidade. Isolar quem se quer convencer ou dissuadir é má estratégia.

Preferimos dar o exemplo e, ao mesmo tempo, agir pela via do diálogo franco -em geral, mais eficaz. No caso do Brasil, essa capacidade de atuar com discrição não é oriunda de algum talento excepcional; é a expressão, em nossas relações com outros Estados soberanos, da natureza conciliadora do povo brasileiro.

AGENDA

Ações desse tipo são bem menos visíveis do que a admoestação midiática exercida por alguns países contra um punhado de governos, selecionados de forma nem sempre criteriosa ou politicamente isenta. A escolha dos indigitados, além de obedecer a agenda política, muitas vezes revela preconceitos, ora religiosos, ora raciais.

Muitos dos países que se consideram modelares cultivam relações com regimes não democráticos, desde que isso corresponda a interesses econômicos ou estratégico-militares. Os exemplos são tantos que não podem escapar ao mais complacente dos olhares.

Além disso, alguns aplicam, eles próprios, a pena capital. Ou conferem tratamento desumano e degradante a trabalhadores imigrantes. Ou ainda transferem suspeitos sem julgamento para prisões secretas, em voos também secretos. Isso para não falar de ações militares unilaterais, à margem do Conselho de Segurança da ONU, que resultam em milhares de vítimas civis.

O Brasil considera que as referências específicas a outros Estados no campo dos direitos humanos devem ser feitas preferencialmente no âmbito do Mecanismo de Revisão Periódica Universal do Conselho de Direitos Humanos das Nações Unidas (CDH), que, aliás, nosso país ajudou a criar.

Ali se busca o tratamento não seletivo, objetivo e multilateral dos direitos humanos em todos os países-membros da ONU.

Em 2011, os métodos de trabalho do CDH serão revisados. Procuraremos aperfeiçoá-los para que o órgão se torne cada vez mais eficaz e para que possa trazer benefícios diretos àqueles que sofrem violações. Em matéria de direitos humanos, como já declarei diversas vezes, não há país que não tenha algo a ensinar, assim como não há país que não tenha algo a aprender.

No esforço de persuadir, o Brasil se vale da cooperação com organizações ou países da mesma região, que têm muito mais probabilidade de serem ouvidos do que, por exemplo, as ex-potências coloniais ou outras nações cuja ação é percebida como reflexo de arrogância e complexo de superioridade.

Destas, pode-se dizer, como na Bíblia, que percebem mais facilmente o cisco no olho do próximo do que a trave em seu próprio olho. Foi o que se revelou quando propusemos, na antiga Comissão de Direitos Humanos, resolução que enunciava que o racismo era incompatível com a democracia.

Tampouco é verdade que o Brasil se recuse a recorrer à condenação quando o diálogo se revela ineficaz.

SEM INDIFERENÇA

O acompanhamento cuidadoso, não movido por preconceitos, de nossas votações no CDH revela que estas estão longe de obedecer a um padrão uniforme e tomam em conta uma variedade de fatores. Muito recentemente, aliás, o Brasil apoiou resolução condenatória a um Estado que se negou a acolher recomendações que tinham por objetivo aperfeiçoar a situação dos direitos humanos no país.

Tampouco é demais lembrar que, por meio da ação multilateral e de projetos de cooperação, o Brasil tem ajudado concretamente na melhora da situação de direitos humanos -no Haiti, na Guiné-Bissau e na Palestina, para citar apenas alguns. As posições do Brasil são fruto de um conjunto bem menos simplório de considerações do que a enganosa dicotomia entre bons e maus.

O Brasil não é indiferente ao sofrimento daqueles que defendem liberdade de expressão ou de culto, dos que lutam pela democracia, dos que se insurgem contra discriminações de toda natureza.

Ao contrário, nossa diplomacia busca constantemente -sem alarde, sem interferências que geram resistências e ressentimentos, mas visando resultados efetivos- atuar em prol da universalização dos valores fundamentais da sociedade brasileira.

CELSO AMORIM é ministro das Relações Exteriores

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário